Common Saltwater Fish and Coral Diseases

A list of saltwater fish diseases and treatments are listed for you. The most effective way to deal with diseases is to prevent it by reducing stress. A varied diet, stable water temperature, good water parameters, daily observance, and responsible stocking are a few ways to ensure healthy fish, free of disease. But even if you manage to deal with it, unfortunately it will still strike one or more of your saltwater fish. Fish will get sick. Pathogens that cause diseases are in and around your fish’s natural setting and in your aquarium. They may be bacterial, viral, fungal or parasitic. So when the fish's skin or tissue gets damaged, whether from shipping, netting or any other circumstances, bacterial and fungal pathogens seize the opportunity to infect the fish. Poor water quality is another reason fish weaken the immune system. This could be another cause for fish diseases.

The bad thing is that there’s not a lot of treatment available for us aquarists and there is no guarantee that our saltwater fish will be saved. We will cover diseases that are most common in your aquarium at home - how you’ll be able to recognize these fish diseases and treatments available.

Saltwater Fish Disease

Table of Common Saltwater Fish Diseases and ProblemsDisease / Problem Symptoms and Treatment

Ammonia Poisoning

Red or inflamed gills. Fish are gasping for air at the surface.

Ammonia poisoning is easily preventable. Avoid adding expensive and

less hardy tropical fish until the aquarium has cycled. For more

information on cycling your aquarium please read about the nitrogen cycle.

You can

use a substance called zeolite or even better Purigen to help absorb ammonia but the best

solution is to ensure that your aquarium has cycled and that your tank

is not overcrowded. If your tank has not yet completed the nitrogen

cycle, you will need to perform frequent water changes to keep the ammonia levels down.

Dropsy

|

| Fish Disease - Dropsy |

- Names: Bloat, Dropsy

- Disease Type: Bacterial (gram negative organism)

- Cause / Organism:Multiple causes

Description:

Dropsy is an old medical term that was once used to describe swelling due to accumulation of fluids in the tissues or body cavities, such as the abdomen. Fish suffering from Dropsy often have a hugely swollen belly, hence the origination of the disease name.

The disease is actually an infection caused by bacteria that are commonly present in all aquariums. Consequently, virtually any species of fish can be stricken with Dropsy. However, healthy fish rarely fall prey to the disease. Fish are only susceptible when their immune system has been compromised by some stress factor. If all the fish in the tank are under stress, it’s quite common for the entire tank to become infected. It is also possible for only one or two fish to fall ill, especially when prompt action is taken to prevent spread of the disease.

As the infection progresses, skin lesions may appear, the belly fills with fluids and becomes swollen, internal organs are damaged, and ultimately the fish will die. Even with prompt treatment, the mortality rate is high. Only fish that are diagnosed in the early stages of the infection are likely to respond to treatment.

The disease is actually an infection caused by bacteria that are commonly present in all aquariums. Consequently, virtually any species of fish can be stricken with Dropsy. However, healthy fish rarely fall prey to the disease. Fish are only susceptible when their immune system has been compromised by some stress factor. If all the fish in the tank are under stress, it’s quite common for the entire tank to become infected. It is also possible for only one or two fish to fall ill, especially when prompt action is taken to prevent spread of the disease.

As the infection progresses, skin lesions may appear, the belly fills with fluids and becomes swollen, internal organs are damaged, and ultimately the fish will die. Even with prompt treatment, the mortality rate is high. Only fish that are diagnosed in the early stages of the infection are likely to respond to treatment.

Symptoms:

Symptoms vary widely. Some fish present with the classic swollen belly, others display skin lesions, while still others show few symptoms at all. This variability is what makes diagnosis difficult. However, in most cases a number of symptoms are observed, both physical and behavioral. Those include:

- Grossly swollen belly

- Scales stand out (pinecone appearance)

- Eyes bulge

- Gills become pale

- Anus becomes red and swollen

- Feces pale and stringy

- Ulcers form on the body along the lateral line

- Spine may become curved

- Fish clamps fins

- Fish becomes lethargic

- Fish stops eating

- Fish hangs near the surface

Cause:

The bacterial agent that causes Dropsy is one of several gram negative bacteria commonly present in aquarium habitats. The underlying cause of fish becoming infected in the first place is a compromised immune system that leaves the fish susceptible to infection. This can happen as the result of stress from a number of factors, such as the following:

- Poor water quality

- Ammonia or nitrite spikes

- Large drop in water temperature

- Stress from transportation

- Improper nutrition

- Aggressive tankmates

- Other diseases

Treatment:

Dropsy is not easily cured. Some recommend that all affected fish be euthanized to prevent spread of the infection to healthy fish. However, if detected early it is possible to save affected fish. Treatment is geared towards correcting the underlying problem, and providing supportive care to the sick fish.

- Move sick fish to a hospital tank

- Add salt to hospital tank, 1 tsp per gallon

- Feed fresh high quality foods

- Treat with antibiotics

Antibiotics should be used if fish do not immediately respond. A broad spectrum anti-biotic specifically formulated for gram negative bacteria is recommended. My preference is for Maracyn-Two . A ten day course is ideal for ensuring the infection is eradicated. However, you should always follow manufacturers directions for duration and dosage.

Prevention:

As in many diseases, prevention is the best cure. Almost all the factors that stress fish enough to cause them to be susceptible to infection can be prevented. Because poor water quality is the most common root cause of stress, tank maintenance is critical. Other factors to keep in mind include:

- Perform regular water changes

- Keep the tank clean

- Clean the filter regularly

- Avoid overcrowding the tank

- Do not overfeed

- Use flake foods within one month of opening

- Vary the diet

A common contributing cause is the flagellate parasite Hexamita. This parasite primarily infects the intestinal tract, but then spreads to the gall bladder, abdominal cavity, spleen, and kidneys. As the disease progresses, the classical lesions of hole in the head disease appear. These lesions will open up and may discharge small white threads that contain parasitic larvae. Secondary bacterial or fungal infections may then develop in these openings and may lead to a more serious disease, and death.

Another popular theory is that a mineral or a vitamin imbalance may contribute to the development of this disease. Some aquarists have claimed a link between the use of activated carbon and an increase in the disease. Some people feel that the carbon may remove some of the beneficial minerals found in the water leading to an increased incidence in the disease. At the same time, the mineral imbalance may be caused by an increase in Hexamita organisms in the intestine, which may lead to malabsorption and a decrease in the absorption of the needed vitamins and minerals.

Conditions that create stress will also increase the incidence of this disease. Poor water quality, improper nutrition, or overcrowding are all stressors that can cause a problem. Because the disease is often associated with older fish, there may be a link with decreased function of the immune system in these older fish and an increase in the incidence of the disease.

Signs

The signs include pitting-type lesions on the head and lateral line. The condition may be mild at first, but if changes to the environment and treatment are not initiated, the holes will become larger and secondary bacterial and fungal infections will develop. These lesions can eventually create a severe infection and the fish becomes systemically ill with loss of appetite and death.

Treatment

Because there may be multiple causes of this disease, the treatment usually consists of taking a multi-faceted approach. The goal is to rid the fish of Hexamita, improve water quality, and improve vitamin/mineral supplementation and nutrition.

A common treatment for infection with Hexamita includes the addition of the antibiotic metronidazole to the treatment tank housing the infected fish. Water quality must be closely watched, and the water quality adjusted to the exact standards required for the fish. Improving nutrition by adding fresh or frozen meaty foods or vegetables in the form of seaweed strips or lightly steamed broccoli may help. Make sure to target the nutrition to the species you are treating. For example, some cichlids are primarily vegetarians, whereas oscars are carnivores. In cases where secondary bacterial infections are present, additional antibiotics such as Maracyn, Kanacyn, or Furan may be needed. When treating this or any disease, try to use a separate treatment tank and treat as soon as the first symptoms appear.

Prevention

Prevention primarily focuses on reducing any stress affecting the fish. Stress, whether in the form of parasites, poor nutrition, or poor water quality all cause a suppression of the fish's immune system, which makes them more susceptible to this or any other disease.

If you own cichlids, oscars, or discus this is a disease that may occur in your tank. Be able to recognize the disease and take prompt steps to initiate early treatment; provide optimum water conditions; and feed the best possible diet. If managed and maintained properly, your fish should improve and not develop the disease again in the future.

Marine Ich or Ick (Cryptocaryon)

Small white spots showing up mainly on the fins or in advanced cases it

may look like your fish has salt all over it. The fish may seem to

"flash" or rub against objects in the tank.

This is a fairly common fish disease and your local pet store or

online store should have medication you can use. Ich usually arises due

to stress. Many believe that you can increase the temperature of your

water to 82 degrees Fahrenheit to speed up the cycle time of this

parasite. Remove any carbon filtration before using medication

(rid-ich) because the carbon will absorb the medication. Try to prevent

this from happening by quarantining your fish in a separate tank before

introducing them into your main tank. Saltwater ich is treatable if

caught in the early stages. Move the fish to quarantine and medicate

according to the directions on the bottle.

Nitrite/Nitrate Poisoning

Tropical fish are lethargic or resting just below the water surface and

you are getting high readings on your nitrite/nitrate test kits.

Nitrite / Nitrate poisoning is not a disease but will kill your tropical

fish. It results from having a large bio-load on the filtration system

or from not performing enough water changes. Perform a partial water

change immediately and monitor the nitrite and nitrate levels closely

until the situation is resolved. You may have too many fish in the tank

and will need to perform more frequent water changes.

Oxygen Starvation

Most or all of the fish are usually found at the water surface. They may be gulping at the surface with their mouths.

Check the temperature of the water. Higher water temperatures require

higher levels of oxygen. You will need to increase the aeration in the

tank with air stones or increase the flow rate with your filters. Try

to decrease the temperature of the water by floating ice cubes in

plastic baggies and turning off the tank light.

If sun light is entering the tank from a nearby window, try closing

the shades. Also, if you have an overcrowded aquarium you will

definitely need to increase the aeration in your tank.

Velvet (Oodinium)

Marine velvet disease is one of the most common diseases that affects marine aquarium fish. It is known by a variety of names including; amyloodiniosis, marine oodinium disease, oodiniosis, and gold dust disease. The scientific name of the infecting organism is Amyloodinium ocellatum.Amyloodinium is a one-celled organism called a dinoflagellate because it has whip-like structures (flagella) which help it move. It is highly adapted to parasitism. There are many free-living dinoflagellates present in most aquatic environments, but this particular species is one of the few that will actually cause disease in fish. This disease is widespread and can cause serious illness and death in aquarium fish if not recognized and treated quickly and properly. This article will give a description of the disease and offer treatment and prevention strategies.

Risk factors

The number of organisms: Amyloodinium is present in a free-swimming and infective form in many aquatic environments. The organism is extremely hardy and can withstand a wide variety of salinity and temperature fluctuations. In the wild, the number of infective organisms that are found in the water in any particular area is very small. In aquarium environments, there is the potential for large numbers of organisms to be found in a very confined space.

The immune system of the fish: As with almost all parasitic infections, most fish can fight off minor infections providing their immune system is strong. Many fish that are caught from the wild, however, and then placed in an aquarium are very stressed and their immune systems are not able to fight off minor infections let alone the greatly increased numbers that may be present in an aquarium environment. Amyloodinium can infect any fish at any time, but it appears to be much more of a problem when new fish are brought into an aquarium. Adding a new fish to an aquarium is obviously very stressful for the new fish and can be stressful for the existing tank inhabitants as well. Fish that are properly quarantined and fed are not as stressed and are much less likely to become infected with the disease and to create an outbreak when transferred to the existing display tank.

Symptoms

The symptoms of marine velvet usually involve the skin and lungs. Mild infections will usually only infect the gills and the fish may show minimal symptoms. As the infestation becomes more severe, the gills will become inflamed, bleed, and the lung tissue will begin to die. The fish will show signs of irritation and distress, with rapid breathing and lethargy. As the inflammation increases, the fish will lose its ability to transport oxygen across the gill membranes resulting in a fish that shows symptoms of suffocation, and if treatment is not initiated, death will often result.

The skin is the site of attachment for the organism and in severe infections, small gold-colored spots will cover the skin, which can progress to create a "velvet" appearance which gives the disease its name. By the time the gold-colored velvet appears, however, the gills may be so infected that treatment is usually too late. Many fish die from this disease without ever showing any visible skin changes. It may be possible to visualize early forms of the infection on the skin by using indirect illumination. This works best on dark fish and can be done by shining a flashlight on the dorsal surface of a fish in a darkened room. Viewing infected fish against a dark background may also be helpful.

Life cycle

|

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually made based upon history and symptoms, but scrapings of the skin can be performed and the trophonts identified. Another technique is to place the infected fish in fresh water for several minutes and the organisms will drop off and float to the bottom. The surface water can be poured off and the sediment can be examined microscopically.

Treatment

Initiate treatment immediately because the disease has such a high mortality level if not treated quickly. Treatment for this disease is almost exclusively with copper. There has been some success reported with the use of the antimalarial drug chloroquine diphosphate but the drug is expensive, difficult to obtain, and therefore not a common treatment option. Copper comes in several forms including ionic and chelated forms. The chelated forms are supposed to be safer but the total amount used is higher, possibly offsetting the safety benefits.

Copper is very effective but can be ineffective or toxic if not used at very specific levels. Choose a high quality product, follow the directions closely, monitor the copper levels in the water, and adjust accordingly. When copper is used, the water should be tested twice a day for copper levels for the first few days, and then daily for the rest of the treatment period. Most sources recommend an ionic copper level of between 0.15 and 0.2 parts per million for a minimum of 14 days. Alkalinity and the presence of carbonate-containing substrates can impact the absorption and release of free copper in the water.

Copper is extremely toxic to invertebrates and should not be used in tanks where invertebrates are, or will ever be, housed. It is always best to use copper or any treatments in a quarantine tank and to only treat the infected fish. IfAmyloodinium does develop in a reef tank with invertebrates, it will be very difficult to rid the tank of theAmyloodinium as long as fish are present. Removing the fish to a separate tank and allowing the tank to run fish-free for a month is probably necessary. This will allow the organism to run through its life cycle and die out due to the lack of a host.

If Amyloodinium does strike your tank, you will want to make sure that the water quality and nutrition are at the highest possible levels. Do everything possible to reduce the stress level of your fish to allow their immune systems to fight off this disease. There is evidence that fish that contract Amyloodinium and recover develop some lasting immunity to the disease.

There are several very important things to remember when treating this disease:

- Stressed fish are much more likely to develop the disease.

- This disease is highly contagious.

- The key to treating this disease is early detection and prompt treatment.

- Most fish that show the severe skin form are probably too sick to respond to treatment.

- Only the free-swimming dinoflagellate form of the organism (the dinospore) is susceptible to treatment.

- Properly sized UV sterilizers will also kill the dinospores.

- The encysted form is not susceptible to any treatment.

Prevention

Prevention is the best way to treat marine velvet disease.

Prevention is truly the best way to treat this disease. We know that this disease is extremely contagious, widespread, and targets stressed fish. This disease most commonly shows up in newly purchased fish but will then often spread to other fish in the tank. Remember that adding a new fish to a tank is stressful for the existing inhabitants as well, and if a new fish comes in with an existing case of marine velvet disease, many of the other fish in the tank could develop the disease. Quarantining new fish is one of the best things you can do to maintain the health of your tank and is critical in preventing outbreaks of marine velvet disease. A quarantine period of a few weeks in a properly functioning quarantine tank will allow the aquarist enough time to ensure the new fish is not harboring velvet or ich. In addition, quarantined fish can be hand fed, isolated from aggressive fish, and treated, if necessary, allowing them to get through this high stress time in the best possible condition. The first several weeks after entering the new home is the highest period of mortality and disease in marine fish. It is impossible to be too careful or spend too much time or effort during this critical time period.

Amyloodinium is a common and deadly disease, but if proper quarantine procedures are followed coupled with early recognition and treatment, you can hopefully avoid the damage caused by this disease.

Black Ich

|

| Clown Fish with Ich |

Saltwater Tangs showing small black spots on their sides.

Get a cleaner shrimp and keep your water parameters in line. Ammonia or

nitrites high? Shame on you. Your tank isn't cycled and you have a

whole mess of issues ahead. Wait until the tank has cycled before adding

fish. High nitrates? Vacuum the sand and clean out the filters, empty

protein skimmer more frequently. Also give those tangs more seaweed in

their diet.

Symptoms

Flicking and scratching against rocks and other surfaces, small white spots resembling sugar covering fins and body. Small black dots (larvae) appear on the sides and fins of affected fish. They may have rapid breathing and stop feeding. Affected fish will scratch themselves on surfaces and swim erratically. They may also breathe abnormally and lose their appetite.

Description

This disease is highly infectious and can spread rapidly to other fish in the tank. Rapid treatment is highly recommended. If treated in a reasonable amount of time it is usually not fatal.

Treatment

If the infestation is minor, a 5-minute freshwater bath may prove effective. Discontinue the freshwater bath if the fish begins to become overly stressed. For more major infestations, use copper-based medications to kill the cryptocaryon parasites. In a reef tank environment, the infected fish must be moved to a hospital tank for treatment. Never add copper compounds to an aquarium containing invertebrates. Some new treatments have appeared on the market recently that claim to control parasites in the marine aquarium. Consult your local aquarium dealer for more information.

Prevention

Insure good water quality and temperature parameters to prevent animals from getting stressed. Stress breaks down the protective mucous coating on a fish and allows parasites to gain a foothold. Additionally, any new fish should be given a short freshwater bath and kept in a quarantine tank for two to three weeks before being introduced into the main aquarium. The use of an ultraviolet sterilizer has also been shown to help prevent outbreaks of this disease.

Cause: Planarian; Ichthyophaga sp., Paravortex sp.

Description

Flukes can infect fish by attaching to the gills or body wall and sucking blood or body fluids. Hooks generally attach the parasite to the host. Those flukes that are monogenetic are able to reproduce in an aquarium and become a problem. Larvae are free swimming and find a host to which they attach. Adults are able to crawl from host to host - they are unable to swim. If a fish knocks them off they will likely die because they must crawl to another host.

At least 2 genera, Paravortex or Ichthyophaga, can cause tang turbellarian, a fairly common disease. The larvae appear as tiny black dots on the surface of a brightly colored fish, feeding on the blood of their host. The worm releases from the host and falls to the tank bottom to become an adult, which reproduces to make free-swimming worms that find new hosts. Repeated cycles of reproduction can produce heavily infected fish.

Treatment: As the flukes are dislodged by treatment, care must be taken to avoid knocking them off in the main aquarium which may allow them to reach another host. Treatment should be done in a hospital tank:

- Freshwater baths, with formalin and malachite green. Parasites will fall off and should be destroyed.

- Praziquantel: 1-5 mg/L hospital tank.

- Trichlorfon (Dylox®) 1.0 mg/L daily for 3 days.

Drug Details For The Treatment of Tang Turbellarian, Black Ich, Black Spot Disease:

| Name | Dosage | Action | Precaution | Dangers |

| Formalin | 37% stock, .03 ml/L prolonged; 0.125 - 0.25 ml/L for brief dips | enzyme and cell membrane protein disruption | toxic to fish and humans | algae, invertebrates, fish above 80°F |

| Malachite green | 2 mg/l brief dip, 0.1 mg/L continuous | binds and denatures intracellular proteins | carcinogenic, toxic | poisonous to fish |

| Freshwater Dip | equalize pH, temperature, 5 minute limit | causes osmotic imbalance that leads to plasmolysis - rupture of the cell | toxic procedure, difficult to move and handle sick fish without harming them further | not used on fish with open wounds |

| Praziquantel | 1 mg/L/3-5 days aqueous; 2.5 mg/1 g food orally | either causes calcium imbalance and parasite paralysis or prevents parasite purine sysnthesis | must be used in a hosptital tank | kills some invertebrates, such as feather duster worms |

Marine Velvet Disease

Other Names: Saltwater Ich, Coral Fish Disease,

Oodinium, Amyloodinium OcellatumSymptoms: Flicking and scratching against rocks and other surfaces, rapid breathing, tiny white spots covering the body that give it a white velvet appearance.

Description: This is without a doubt the most infectious and deadly marine fish disease. The tiny parasites multiply quickly and eventually move into the gill plates of the fish causing slow suffocation. It can easily spread to other fish in the tank. If not treated immediately, it can cause death in only a few days. Rapid treatment is mandatory for the survival of the fish.

Treatment: Use copper-based medications to kill the amyloodinium parasites. In a reef tank environment, the infected fish must be moved to a hospital tank for treatment. Never add copper compounds to an aquarium containing invertebrates. Some new treatments have appeared on the market recently that claim to control parasites in the marine aquarium. Consult your local aquarium dealer for more information.

Prevention: Insure good water quality and temperature parameters to prevent animals from getting stressed. Stress breaks down the protective mucous coating on a fish and allows parasites to gain a foothold. Additionally, any new fish should be given a short freshwater bath and kept in a quarantine tank for two to three weeks before being introduced into the main aquarium. The use of an ultraviolet sterilizer has also been shown to help prevent outbreaks of this disease.

Black Spot Disease

SymptomsFlicking and scratching against rocks and other surfaces, small black spots on the body.

Description: This disease is caused by small parasitic worms. The black spots are usually not as numerous as those in white spot disease. Also, black spot disease is not nearly as deadly.

Treatment

If the infestation is minor, a 5-minute freshwater bath may prove effective. Discontinue the freshwater bath if the fish begins to become overly stressed. For worse cases, use a copper or trichlorofon based solution. In a reef tank environment, the infected fish must be moved to a hospital tank for treatment. Never add copper compounds to an aquarium containing invertebrates. Some new treatments have appeared on the market recently that claim to control parasites in the marine aquarium. Consult your local aquarium dealer for more information.

Prevention: Insure good water quality and temperature parameters to prevent animals from getting stressed. Stress breaks down the protective mucous coating on a fish and allows parasites to gain a foothold. Additionally, any new fish should be given a short freshwater bath and kept in a quarantine tank for two to three weeks before being introduced into the main aquarium. The use of an ultraviolet sterilizer has also been shown to help prevent outbreaks of this disease.

| Fish Disease Gill Flukes |

|

| Fin flukes fish Disease |

Description: This is another disease that is highly infectious and can be fatal if not treated quickly. It is caused by small worm-like parasites. They multiply quickly and can clog the gill of the fish causing slow suffocation.

Treatment: A freshwater bath will provide immediate relief for the fish by killing most of the parasites. A long saltwater bath with methylene blue is also helpful. Some new treatments have recently been introduced. Contact your local aquarium dealer for more information about these.

Prevention: Insure good water quality and temperature parameters to prevent animals from getting stressed. Stress breaks down the protective mucous coating on a fish and allows parasites to gain a foothold. Additionally, any new fish should be given a short freshwater bath and kept in a quarantine tank for two to three weeks before being introduced into the main aquarium. The use of an ultraviolet sterilizer (UV Sterilizer) has also been shown to help prevent outbreaks of this disease.

Virus and Bacterial Infections

Bacterial Finrot

Symptoms: Erosion of fins and fin rays, reddened

areas, lethargy, poor appetite. |

| Freshwater Fish Fin Rot Fish Disease |

Description: This disease is usually associated with stress, sometimes brought on by poor water quality. Healthy animals can usually resist infections. Finrot usually begins as a mild external infection causing a reddening of the base of the fins. In severe cases, the animal's body and mouth may be eaten away.

Treatment: Identify the source of stress and correct the problem. If this does not correct the problem, the animal should be treated with antibiotics or Melafix in a hospital tank. Adding antibiotics to the main aquarium can kill invertebrates and damage the biological filter. Melafix for maar20ine environments are usually always reef safe but look for it stating that on the bottle. Follow the instructions.

|

| Marine Fin Rot Bacterial |

Prevention: Insure good water quality and temperature parameters to prevent animals from getting stressed. Stress breaks down the protective mucous coating on a fish and allows bacteria to gain a foothold. The use of an ultraviolet sterilizer may help prevent outbreaks of this disease.

Bacterial Infection

Other Names: Pseudomonas,VibrioSymptoms: Reddened, frayed fins with open sores, rapid respiration, cloudy eyes, poor appetite, lethargy, weight loss, abdominal swelling.

Description: This disease is usually associated with stress, sometimes brought on by poor water.

quality. Healthy animals can usually resist infections.

Treatment: Identify the source of stress and correct the problem. If this does not correct the problem, the animal should be treated with antibiotics in a hospital tank. I prefer to use Melafix by adding antibiotics to the main aquarium it is invert and reef safe.

Prevention: Insure good water quality and temperature parameters to prevent animals from getting stressed. Stress breaks down the protective mucous coating on a fish and allows bacteria to gain a foothold. The use of an ultraviolet sterilizer may help prevent outbreaks of this disease.

Symptoms: Small warty clumps on the fins that resemble small cauliflowers.

Description: This disease is caused by a virus and often looks worse than it is. It is rarely fatal and will usually clear up on its own if optimum water quality is maintained.

Treatment: There is no effective treatment for this disease. A short freshwater dip may help. Maintain optimum water quality and symptoms should improve with time. If a secondary bacterial infection should occur, move the animal to a hospital tank and treat with antibiotics.

Prevention: Insure good water quality and temperature parameters to prevent animals from getting stressed. Stress breaks down the protective mucous coating on a fish and allows the virus to gain a foothold. Additionally, any new fish should be given a short freshwater bath and kept in a quarantine tank for two to three weeks before being introduced into the main aquarium.

Other Aquarium Diseases

Marine Fungus

Other Names: Ichthyophonus, CNS DiseaseSymptoms: Darkening in color, sandpaper appearance of skin, poor appetite, listlessness.

Description: Fungal spores are present in all aquariums but, if you are not careful, they can become a problem in the saltwater tank.

When cultivating a saltwater aquarium there are a variety of elements you must monitor and control. In addition to keeping your water quality high and your salinity levels stable, you also have to be on the lookout for harmful bacteria and fungus entering the tank. While most aquariums naturally contain some fungus and bacteria, if these organisms are allowed to grow out of control they could contribute to a number of problems in your tank. Filamentous fungus, for example, can be a serious problem in the marine tank. Other forms of fungus may include fungal infections which affect the bodies of fish and egg fungus which can quickly kill fish eggs. To prevent fungus from causing problems in your saltwater aquarium, take the time to learn the basics about how these infections start and what you can do to prevent them.

What is Marine Fungus?

What is Marine Fungus?

Live marine fungus typically consists of a mass of threadlike filaments called hyphae that grow together in clumps to form mats. Certain types of fungus grow downward into the organic matter on which they are feeding, acting much like the roots of live plants. Other types of fungus grow outward, spreading in the form of fluffy growths. As the fungus grows and spreads, sporangia will form on the tips of the filaments – these sporangia contain spores which will be released into the tank water when the sporangia mature and rupture. Fungus feeds on all kinds of organic matter – fish waste is one the most common foods that they ingest, along with uneaten fish food. Certain types of fungus also exhibit parasitic qualities, feeding on the bodies of fish that have already been damaged by stress, injury or disease.

Marine Fungal Infections

There are several different types of marine fungus, some of which are normally harmless to aquarium fish. Saprolegnia fungi, for example, are common in all types of aquariums and they typically feed on organic waste like dead fish and uneaten fish food. In cases of poor water quality, however, this fungus may start to grow on aquarium fish, especially if its gills or skin have already been damaged. Overcrowding and stress in the saltwater aquarium may also increase the likelihood that normally harmless fungus will begin to attack your fish.

The most common type of fungal infection in saltwater and freshwater aquarium sis body fungus – this type of infection is very distinctive and generally easy to diagnose. These fungal infections typically manifest in the form of fuzzy patches growing on the body or fins of infected fish. As the infection spreads, the growths may become enlarged and could begin to take on a green or brownish tint as a result of debris particles becoming trapped on the filaments. Once this type of fungal infection sets in, it can quickly spread throughout the body of infected fish. Though the infection usually does not penetrate any deeper than the superficial muscle and gill layers of the body, it can cause severe damage. Some fungus may also excrete harmful chemicals that can weaken the immune systems of infected fish, leaving them more susceptible to secondary infections.

Treatment Options

The key to dealing with marine fungus in the saltwater aquarium is to take action as soon as you recognize the problem. While you may be tempted to tackle the infection itself first, your first step should be to remedy the underlying cause of the infection. In many cases, fungal infections are precipitated by a drop in water quality or an increase in stress. Test the water in your aquarium to make sure the water parameters are in line and make adjustments if necessary. If you are able to determine that water quality is not the issue, look for other sources of stress in the tank. If one or more of your fish are particularly aggressive, it could cause the rest of your fish to become stressed. Physical injury as a result of aggressive tank mates or unsafe aquarium decorations may also be a problem.

After you have determined and remedied the underlying cause of the fungal infection you can move on to treating the infection itself. You will not be able to completely remove the fungal spores from your aquarium because they are resistant to treatment. Fortunately, it is unnecessary to remove all of the spores from the tank because they will not harm your fish unless they are already weakened by stress or injury. To deal with fungal infections you should quarantine the affected fish in a hospital tank and treat the water with an anti-fungal medication like Pimafix. There are many anti-fungal medications available including malachite green and formalin – salt may also be an effective treatment for some fungal infections. When treating your fish, make sure to remove any activated carbon from your aquarium filter and follow the dosing instructions carefully. If the infection is particularly stubborn, you may need to use potassium permanganate – this product can be toxic in water with a high pH, so use this product very carefully.

Prevention: Insure good water quality and temperature parameters to prevent animals from getting stressed. Stress breaks down the protective mucous coating on a fish and allows the fungus to gain a foothold. Additionally, any new fish should be given a short freshwater bath and kept in a quarantine tank for two to three weeks before being introduced into the main aquarium.

|

| HLLE Fish Disease |

Other Names: HLLE

Symptoms: Erosion of the lateral line and the formation of pits in the skin.

Description: This disease is usually caused by poor environmental conditions and poor water quality. If conditions are not improved, the condition of the fish will slowly deteriorate and the animal may die.

Treatment: Improve environmental conditions, maintain optimum water quality and proper diet. The use of vitamin supplements may help.

Prevention: Insure good water quality and temperature parameters. Maintain healthy diet.

Poisoning

Other Names: NoneSymptoms: Erratic behavior, darting around the tank, rapid breathing, gasping at surface.

Description: This condition can be caused by the introduction or overdosing of medications, heavy metals, chlorine or chloramine, household chemicals, or other toxic substances. Immediate action is required to prevent poisoning or permanent damage.

Treatment: Remove the pollutants from the tank through water changes and the use of filter media such as activated carbon. If the condition is critical, move the animals to a tank with clean water.

Prevention: Maintain proper water quality and try to prevent the addition of external toxins. A cover for the aquarium may help. Follow instructions carefully when using medications.

Malnutrition

Other Names: Poor DietSymptoms: Tendency to bloat after feeding, sunken stomach, thinness, listlessness, loss of color.

Description: The symptoms of malnutrition can be similar to other diseases.

Treatment: Provide a good, varied diet. Use the right kinds of food for each animal. Use of vitamin supplements may also be helpful in recovery.

Prevention: Insure proper feeding and proper diet. Avoid overfeeding.

Aquarium Pests

Other names: Diatoms

Description: Brown algae is a common occurrence in newly set up aquariums. It is not really an algae. It is actually a colony of microscopic creatures called diatoms. Brown algae is usually caused by excess silicates and nitrates in the water. It can also be caused by inadequate lighting. Silicates can be introduced into the water through of tap water. Avoid using tap water if possible. Silicates can also leech from some substrates. Avoid using colored gravel from the pet store. Using aragonite sand or crushed coral as a substrate will help reduce silicate levels.

Treatment: Wipe the glass regularly with a good quality aquarium scraper. Magnetic scrapers are available that will let you clean the glass without having to get your hands wet. Brown algae is commonly caused by excess silicates and nitrates in the water. Check nitrate levels and perform regular water changes with pure quality water.

Prevention: Brown algae usually goes away after a new aquarium becomes established. If you continue to have problems, make sure to perform regular water changes once or twice per month. Regular water changes are the best way to control algae. If you don't have one, install a good quality protein skimmer to remove organic waste. You can also install a phosphate reactor to remove phosphates from the water. Make sure to use pure water. Consider investing in an RO/DI water filtration system. Also, make sure you are using lights that are made for aquarium use. Make sure the bulbs are not too old. Fluorescent bulbs should be replaced every 12 - 18 months. After that, the wavelength of the light changes and can encourage algae growth. Make sure you are not leaving the lights on for more than ten hours each day.

Hair Algae

Symptoms: Long strands of green algae that

resemble hair growing on the rocks, decorations, or filters.Description: Hair algae gets its name from its appearance. It resembles green hair growing in the aquarium. It is caused by an excess of nitrates and phosphates in the water. Once established, hair algae can spread quickly and can completely overcome the tank if not properly treated.

Treatment: Test your water for phosphates and nitrates. If phosphates are high, you can get find a variety of phosphate filter media at your local aquarium store. Follow the directions closely. Do not leave the filter in the water for longer than the suggested use. If left in too long, the filter can actually leak phosphates back into the water. If nitrates are high, perform regular water changes with good quality water. Do not use tap water.

Prevention: Hair can be controlled by maintaining good water quality. Make sure to perform regular water changes once or twice per month. If you don't have one, install a good quality protein skimmer to remove organic waste. You can also install a phosphate reactor to remove phosphates from the water. Make sure to use pure water. Consider investing in an RO/DI water filtration system. Also, make sure you are using lights that are made for aquarium use and that the bulbs are not too old. Fluorescent bulbs should be replaced every 12 - 18 months. After that, the wavelength of the light changes and can encourage algae growth. Make sure you are not leaving the lights on for more than ten hours each day. You may also want to add some herbivores to your tank. Blue-legged hermit crabs, sally lightfoot crabs, tangs, and turbo snails make good choices for controlling algae. If your aquarium is set up for invertebrates, you will want to keep several hermitcrabs and turbo snails as part of your "clean-up crew". You may also want to consider using live sand in your aquarium. Live sand contains microorganisms that can help to remove nitrates from the water.

Description: This is actually a form of algae. The bubbles, also known as vesicles, are small bladders that contain water. These vesicles also contain spores. When the vesicle grows large enough, it will pop and release thousands of spores which will travel around the aquarium to form new vesicles. Bubble algae of a number of different species with slightly different shapes and colors, but they all pretty much have the same characteristics. Bubble algae is notoriously hard to eliminate once it gets established.

Treatment: The first step for treatment is to manually remove as much of the algae as possible. Carefully remove the bubbles using a sharp instrument such as a sharpened screwdriver or razor blade. Be careful not to pop the bubbles as this can actually help the algae spread. Part two of the treatment involves the use of herbivores. Emerald crabs can be particularly useful eliminating bubble algae and preventing its return. Hermitcrabs and sally lightfoot crabs can also be useful. It has been reported that some red-leg hermit crab species will also eat bubble algae.

Prevention: Prevention of bubble algae is pretty much the same as for all algae. You must reduce the algae's food supply by removing nutrients from the water. A really good protein skimmer is a good investment for any serious aquarist. A phosphate reactor can also help to remove excess nutrients from the water. Regular water changes are also necessary if you want to prevent algae from growing. Make sure to use pure water. Consider investing in an RO/DI water filtration system.

|

| Cyanobacteria |

Other name: Cyanobacteria

Description: This is not actually an algae at all. It is a form of bacteria known as cyanobacteria. It is one of the oldest forms of life on earth and may represent an evolutionary link between bacteria and algae. It may start out in small patches and slowly spread throughout the aquarium.

Treatment: Commercial antibiotic treatments for slime algae are available at your local aquarium store. They vary slightly from one brand to the next, so make sure you read the instructions thoroughly and follow the directions exactly. Improper use of antibiotics can affect the beneficial bacteria that filter the water. Monitor ammonia and nitrite levels after use to make sure your biological filtration has not been damaged. Most of these treatments are safe for use in a reef aquarium as long as you follow the directions exactly. When used properly, these treatments are effective for controlling slime algae outbreaks.

Prevention: Slime algae is usually caused by high levels of nutrients and organic waste in the water. Make sure to perform regular water changes once or twice per month. Regular water changes are the best way to control algae. If you don't have one, install a good quality protein skimmer to remove organic waste. You can also install a phosphatereactor to remove phosphates from the water.

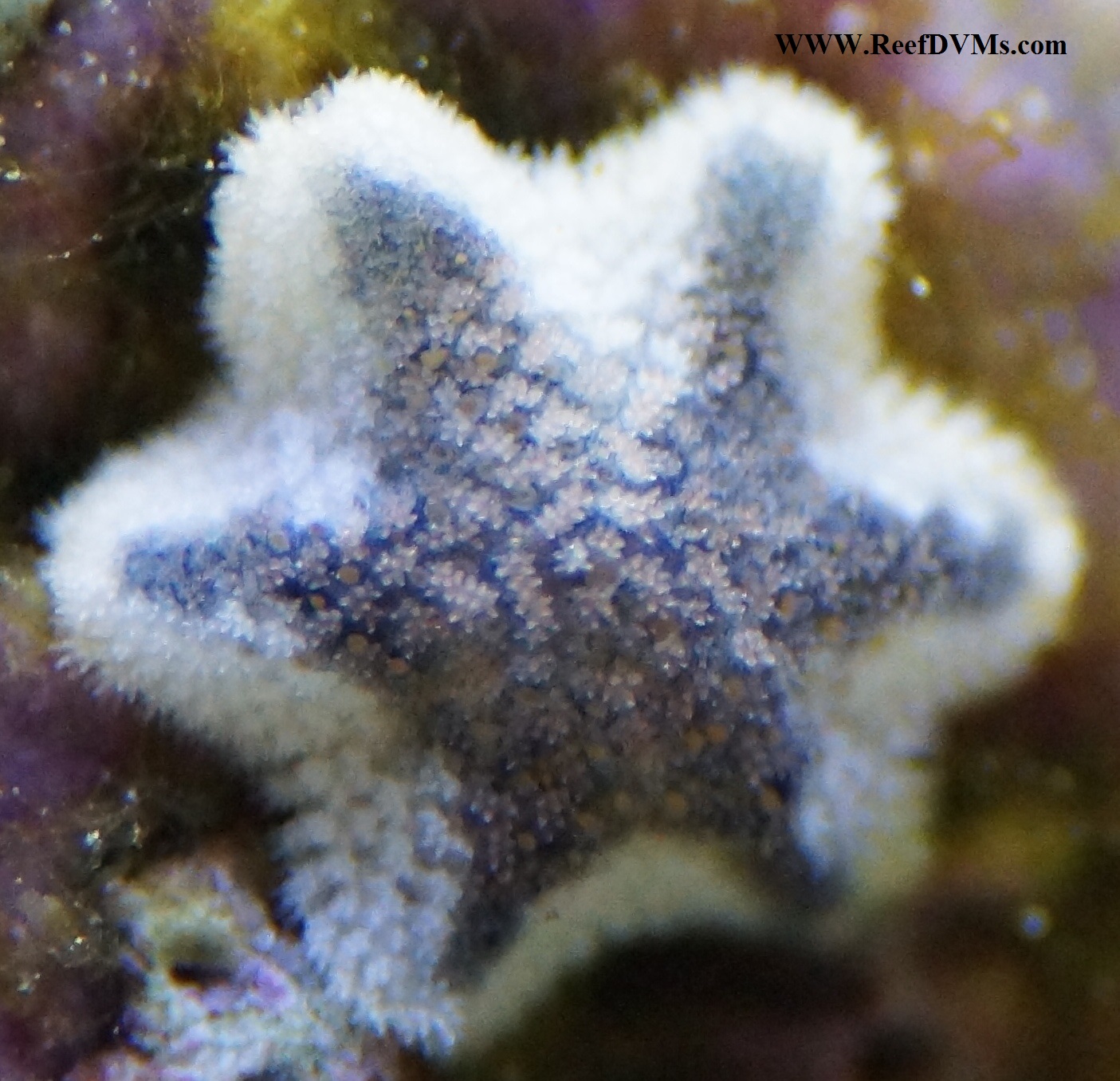

Description: These starfish are known as asterina. They are an invasive species that is commonly added to the aquarium as a hitchhiker on live rock or coral when it is added to the aquarium. The starfish multiply by breaking off their legs. Each leg that breaks off will grow into a new starfish in a matter of days. Once introduced, asterina can quickly overcome a reef tank and can decimate your coral. There is some debate within the aquarium community as to whether asterina will eat coral. There is a large debate on these little guys. I have some and they are not a problem. Others say they can eat your zoas and corals. I have never personally seen that. It started out with just a few starfish and then within months there were literally thousands of them. I recently had an outbreak in my aquarium and within a few months all of my zoanthids had completely disappeared. I also lost a torch coral. They even removed nearly all of the coralline algae from my live rock.

Treatment: The only effective treatment for an asterina invasion is control by means of the harlequin shrimp. The diet of the harlequin shrimp consists solely of starfish. I added two harlequin shrimp to my reef aquarium and within six months the asterina were gone. But remember when the starfish are gone they are starving. you might want to lend this animal around or trade out at your LFS. If you have any other starfish in your aquarium, you will have to remove them before adding the harlequin shrimp. They will eat every starfish they can find.

Prevention: Since asterina are introduced to the aquarium as hitchhikers, the only known prevention method is to thoroughly examine every piece of coral or live rock before introducing it to your aquarium. Remove any asterina stars you may see in your tank before they multiply to biblical proportions.

Description: Aiptasia are one of the banes of the marine reef aquarium hobbyist. They are an invasive species that is commonly added to the aquarium as a hitchhiker on live rock or coral when it is added to the aquarium. They multiply quickly and can take over a reef aquarium if not treated. They can sting fish and damage corals. Larger anemones have even been known to catch and eat smaller fish.

Treatment: When treatment of aiptasia you have two choices: chemical or biological. Chemical treatments are commercially available that can work quite well if you are persistent. They are marketed under names like Joe's Juice or Aiptasia X. I have had good results with Aiptasia X. The only thing is that you have to insert the tip of the syringe directly into the mouth of the anemone in order to kill it or it will just spread. This can be challenging and may take a few times to actually succeed in accomplishing that. These products are applies directly to the anemone using a small syringe. Within minutes the anemone will shrivel and implode. The only problem with these products is that the anemone will grow back, so you have to be diligent and keep using it until they are gone. The products are safe for use in a reef aquarium. A biological treatment is also available in the form of a fish. The aiptasia eating filefish, or matted filefish (Acreichthys tomentosus) will eat the anemones and can completely clean out a serious infestation in a matter of months. I personally keep the copperbanded butterfly fish. It might take a little time to get them to eat it but when they do your tank will be aiptasia free. I would suggest going with the Aiptasia X for small infestations and the filefish or copperbanded butterfly fish for large infestations.

Prevention: Since aiptasia are introduced to the aquarium as hitchhikers, the only known prevention method is to thoroughly examine every piece of coral or live rock before introducing it to your aquarium. Treat any aiptasia with Aiptasia X or similar remedies as soon as you see them to prevent them from spreading and becoming a problem.

Coral Diseases and Syndromes

Reports

of coral disease are increasing in the wild and have often been linked

to changes in the climate, specifically rise in sea temperatures. In

aquarium systems diseases are also a major cause of concern and often

result in mortality. Small coral frags can often die overnight and there

is not usually much chance of a remedy. However in cases with reef

tanks containing larger colonies, diseases can take longer to take

effect and many blog sites report attempts at curing these diseases,

from fragmentation, quarantine, administration of antibiotics or

commercial products aimed at specific diseases. Here we report the main

diseases commonly associated with aquarium diseases and suggest

potential causes and likely ways to manage or mitigate them.

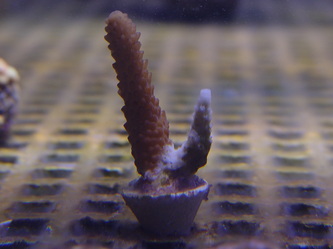

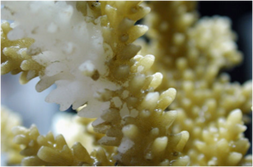

White Syndrome

Background:

White Syndrome (WS) is a collective term for coral disease lesions showing a sharp demarcation

between apparently healthy coral tissue and the bare coral skeleton,

where the tissues have been removed rather than becoming pale or

'bleached'. You often need to look very close (sometimes with the aid of

a magnifying glass) to distinguish between the two and tell whether

there are any coral tissues still covering the skeleton. This disease,

if left alone, will often result in total colony mortality, with the

lesion advancing more quickly as it progresses to the last remaining

fragments of live tissues. WS has been reported worldwide in the wild

and in aquaria. WS displays variable rates of lesion progression and

patterns of tissue loss, which has led to numerous alternative

descriptions and definitions. The two most commonly referred to with

regard to aquarium corals are: Rapid Tissue Necrosis and Shut Down

Reaction.

Causes:

Most

scientific papers and blog sites will accredit this disease to bacteria

of the genus Vibrio. However, it is not clear whether these are primary

pathogens causing the disease or secondary colonisers invading the

tissue once other microbes have caused damage. Relatively high

abundances of Vibrio species live in healthy coral tissue and

environmental samples such as aquarium sand. Recent research (Sweet

& Bythell 2012) has shown the presence of protozoan's known as

ciliates in corals showing signs of WS, and these ciliates can be seen

to ingest the coral's endosymbiotic algae (zooxanthellae), suggesting an

active role in WS pathogenesis. So the actual microbial agent

responsible for WS has not been satisfactorily identified, and there may

be several agents working in parallel.

Management or Mitigation:

Fragmentation

of the coral at least 1 cm above the disease lesion is currently the

best method to save parts of colonies affected by this disease. Other

treatments such as freshwater dips (15ppt), iodine dips (use 40 drops

per 4.5 litres and immerse coral for 10-15 min), sealing of the disease

lesion with marine putty and antibiotics and/or natural extracts such as

tea tree oil have been shown by a few to succeed. However it likely

depends on the size of your colony and how quickly you catch it - corals

that are already immunosuppressed will often not reposnd well to

further treatments. Isolation of any samples showing this disease will

stop the spread to other corals. However, the underlying cause of the

disease is usually a physiological stress, so always check and adjust

aquarium water parameters when needed if WS develops.

Brown Jelly Syndrome

Background:

Brown Jelly

Syndrome (BJS) is, as the name suggests, characterised by a brown mass

resembling jelly. It appears to be floating on the surface of the coral

and moves. This disease is also often associated with a rotten smell if

handled. BJS appears to be restricted to aquaria and no reported wild

diseases are similar in appearance. Tissue loss is fast and the disease

is very contagious, so can spread to other corals regardless of

species.

Causes:

Although

the underlying cause may not be known, the pathology of this disease is

characterised by very large numbers of the ciliate commonly referred to

as Helicostoma nonatum. However, recent research shows these

ciliates to be identical to the same ciliates associated with WS in both

aquaria and in the wild (Philaster sp.) and closely related to

ciliates associated with another wild disease called Brown Band Disease

(BrB) which has been associated with Philaster guamensis.

While ciliates are undisputedly present in the brown jelly material associated with BJS, it remains unclear as to what exact role they play in the disease pathology (i.e. are they the primary causal agents or secondary invaders?). This is also the case for the wild type disease BrB. It is feasible they are only present because they are feeding on dead tissue arising from another pathogen or non-pathogenic disease (Borneman & Lowrie, 2001). In support of this, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) has often but not always isolated Vibrio spp. particularly V. vulnificus from corals such as Goniopora and Euphyllia exhibiting disease signs similar to BJS (Pers obs), however further work needs to be conducted.

While ciliates are undisputedly present in the brown jelly material associated with BJS, it remains unclear as to what exact role they play in the disease pathology (i.e. are they the primary causal agents or secondary invaders?). This is also the case for the wild type disease BrB. It is feasible they are only present because they are feeding on dead tissue arising from another pathogen or non-pathogenic disease (Borneman & Lowrie, 2001). In support of this, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) has often but not always isolated Vibrio spp. particularly V. vulnificus from corals such as Goniopora and Euphyllia exhibiting disease signs similar to BJS (Pers obs), however further work needs to be conducted.

Management or Mitigation:

As with WS,

the use of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as chloramphenicol

(Tifomycine:flexyx.com, only available in USA) and metronidazole is

commonly cited. Doxycycline, Oxytetracycline, Iodine and freshwater dips

(15 ppt) have all been used. Low salinity should only be used for large

polyp species, smaller polyp species such as Acropora do not

tolerate low salinity well particularly when they are already stressed

by disease. Removing infected areas of a colony well ahead of the line

of healthy tissue can sometimes stop the infection from spreading but

great care should be taken to siphon off loose tissue first and avoid

spreading infected material around the tank. Isolation of any samples

showing this disease have also been reported to sometimes stop the

spread to other corals.

Brown Band Disease:

A similar disease, often found in the wild is called Brown Band Disease. Recently studies have proven that ciliates like those reported on here associated with both White Syndrome and Brown Jelly Syndrome are indeed the causal agents and often follow after damage to the coral tissue. Below is the abstract of the recent publication by Stefano Katz from Jame Cook University in Australia.

Brown band (BrB) disease manifests on corals as a ciliate-dominated lesion that typically progresses rapidly causing extensive mortality, but it is unclear whether the dominant ciliatePorpostoma guamense is a primary or an opportunistic pathogen, the latter taking advantage of compromised coral tissue or depressed host resistance. In this study, manipulative aquarium-based experiments were used to investigate the role of P. guamense as a pathogen when inoculated onto fragments of the coral Acropora hyacinthus that were either healthy, preyed on by Acanthaster planci (crown-of-thorns starfish; COTS), or experimentally injured. Following ciliate inoculation, BrB lesions developed on all of COTS-predated fragments (n = 9 fragments) and progressed up to 4.6 ± 0.3 cm d−1, resulting in ~70 % of coral tissue loss after 4 d. Similarly, BrB lesions developed rapidly on experimentally injured corals and ~38 % of coral tissue area was lost 60 h after inoculation. In contrast, no BrB lesions were observed on healthy corals following experimental inoculations. A choice experiment demonstrated that ciliates are strongly attracted to physically injured corals, with over 55 % of inoculated ciliates migrating to injured corals and forming distinct lesions, whereas ciliates did not migrate to healthy corals. Our results indicate that ciliates characteristic of BrB disease are opportunistic pathogens that rapidly migrate to and colonise compromised coral tissue, leading to rapid coral mortality, particularly following predation or injury. Predicted increases in tropical storms, cyclones, and COTS outbreaks are likely to increase the incidence of coral injury in the near future, promoting BrB disease and further contributing to declines in coral cover.

A similar disease, often found in the wild is called Brown Band Disease. Recently studies have proven that ciliates like those reported on here associated with both White Syndrome and Brown Jelly Syndrome are indeed the causal agents and often follow after damage to the coral tissue. Below is the abstract of the recent publication by Stefano Katz from Jame Cook University in Australia.

Brown band (BrB) disease manifests on corals as a ciliate-dominated lesion that typically progresses rapidly causing extensive mortality, but it is unclear whether the dominant ciliatePorpostoma guamense is a primary or an opportunistic pathogen, the latter taking advantage of compromised coral tissue or depressed host resistance. In this study, manipulative aquarium-based experiments were used to investigate the role of P. guamense as a pathogen when inoculated onto fragments of the coral Acropora hyacinthus that were either healthy, preyed on by Acanthaster planci (crown-of-thorns starfish; COTS), or experimentally injured. Following ciliate inoculation, BrB lesions developed on all of COTS-predated fragments (n = 9 fragments) and progressed up to 4.6 ± 0.3 cm d−1, resulting in ~70 % of coral tissue loss after 4 d. Similarly, BrB lesions developed rapidly on experimentally injured corals and ~38 % of coral tissue area was lost 60 h after inoculation. In contrast, no BrB lesions were observed on healthy corals following experimental inoculations. A choice experiment demonstrated that ciliates are strongly attracted to physically injured corals, with over 55 % of inoculated ciliates migrating to injured corals and forming distinct lesions, whereas ciliates did not migrate to healthy corals. Our results indicate that ciliates characteristic of BrB disease are opportunistic pathogens that rapidly migrate to and colonise compromised coral tissue, leading to rapid coral mortality, particularly following predation or injury. Predicted increases in tropical storms, cyclones, and COTS outbreaks are likely to increase the incidence of coral injury in the near future, promoting BrB disease and further contributing to declines in coral cover.

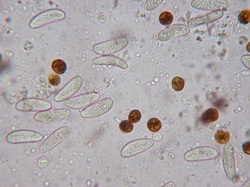

After treatment

After

treatment of corals suffering from BJS with Metronidazole (by Dr

William Wildgoose), the ciliate's were observed to die off and

be completely absent (see picture of brown jelly with no ciliate's

present). If the corals survive remains to be known, it

is likely treatment such as this will work if you catch the disease

early enough. If the coral is to far gone and the disease to wide spread

fragmentation and isolation are still the best bet.

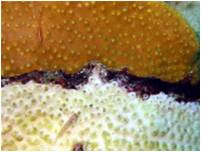

Red Slime Algae or Red Band Disease

Background:

This

disease falls under the broad spectrum of cyanobacterial overgrowth

forming a mat over the aquarium floor and often the corals themselves.

It varys in colour from red, black to blue-green. There are strong

similarities between this disease morphology and that of the

cyanobacterial mat of Black Band Disease within wild coral populations

(Weil, 2004; Weil & Croquer, 2009).

Causes:

This

disease is most commonly associated with high levels of organic

nutrients within the aquarium, which in turn may be influenced by

changes in light levels. Despite the common name of this disease, the

causal agent is not actually an alga at all, but a consortium of

cyanobacteria (photosynthetic filamentous bacteria).

Management or Mitigation:

Red Slime Algae is reported to be treatable by commercial products such as Ultralife Red Slime Remover, Boyd Chemi-Clean, and Blue Life Red Slime Control

(Brang, 2010). However, many of these diseases are reported as a sign

of poor water quality, so most aquarists propose reassessment and

improvement of aquarium water quality (reducing levels of nitrate and

phosphate and monitoring light levels and improving flow) as the most

effective treatment. Because the cyanobacteria are photosynthetic,

masking the band with putty or plasticine has been reported to be

effective in the wild.

Red Slime Algae is reported to be treatable by commercial products such as Ultralife Red Slime Remover, Boyd Chemi-Clean, and Blue Life Red Slime Control

(Brang, 2010). However, many of these diseases are reported as a sign

of poor water quality, so most aquarists propose reassessment and

improvement of aquarium water quality (reducing levels of nitrate and

phosphate and monitoring light levels and improving flow) as the most

effective treatment. Because the cyanobacteria are photosynthetic,

masking the band with putty or plasticine has been reported to be

effective in the wild.Snails

Background:

There

are a few coral-eating snails commonly appearing in aquariums. Most

prey on soft corals. Depending on the snail species, number

of snails and the corals involved, predation can range in severity from

hardly noticeable to devastating.

Causes:

The most common corallivorous snails your likely to encounter are Drupella, Heliacus and Coralliophila

Heliacus - Also known as Box snails. These snails are notorious for feeding on Zoanthids. They have a classic shaped shell that is round at the base and twists upward into a point. Usually smaller than a pea. Tan and brown colouration alternate within the striations of the shell, giving it a rather beautiful appearance. They may or may not become a problem. The Box Snails are guilty of consuming many different types of polyps within the Zoanthus, Palythoa and Protopalythoa genera. Many times the snail will be found within the colony itself, where they puncture the base of the polyp, and feed upon its tissue and fluids. The polyp is then basically left as an empty shell, which quickly falls off of the rock and decomposes. Drupella cornus, commonly known as the horn drupe has a shell size of an adult between 28 - 40 mm. This whitish shell shows four rows of spiny, pointed nodules with numerous smaller spines between. They lay benthic egg capsules, which hatch into free-swimming planktonic larvae. This particular snail is attracted to Montipora corals

Coralliophila abbreviata is known to affect corals in the wild and within aquaria, this particular species is commonly associated with Montastraea sp. and Acropora sp.

Heliacus - Also known as Box snails. These snails are notorious for feeding on Zoanthids. They have a classic shaped shell that is round at the base and twists upward into a point. Usually smaller than a pea. Tan and brown colouration alternate within the striations of the shell, giving it a rather beautiful appearance. They may or may not become a problem. The Box Snails are guilty of consuming many different types of polyps within the Zoanthus, Palythoa and Protopalythoa genera. Many times the snail will be found within the colony itself, where they puncture the base of the polyp, and feed upon its tissue and fluids. The polyp is then basically left as an empty shell, which quickly falls off of the rock and decomposes. Drupella cornus, commonly known as the horn drupe has a shell size of an adult between 28 - 40 mm. This whitish shell shows four rows of spiny, pointed nodules with numerous smaller spines between. They lay benthic egg capsules, which hatch into free-swimming planktonic larvae. This particular snail is attracted to Montipora corals

Coralliophila abbreviata is known to affect corals in the wild and within aquaria, this particular species is commonly associated with Montastraea sp. and Acropora sp.

Management or Mitigation:

Quarantine of the coral and manual removal of the snails is the best treatment (if the snails become a problem).

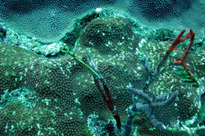

Quarantine of the coral and manual removal of the snails is the best treatment (if the snails become a problem). Red Bugs

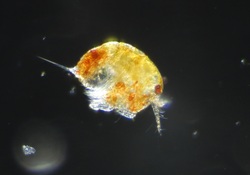

Background:

Infestations from the 'red bug' Tegastes acroporanus is often referred to as a disease/syndrome in most of the grey literature. T. acroporanus is

a predatory micro-crustacean which is specific to acroporids, they are

small, ca. 0.5 mm in length and yellow in colour with a distinctive red

dot which gives this species its common name. Poor polyp extension, loss

of colouration and overall decline in health have been reported as

signs of infection. Infestations of T. acroporanus have so far not been recorded in the wild to date, although would be easily overlooked due to their size.

Causes:

As the name suggests, this is caused by large numbers of T. acroporanus.

As this parasite is now widely distributed in the marine aquarium

industry it is easily transferred between aquaria by the exchange of

cultivated colonies. Great care should be taken when receiving Acropora colonies from another collection to quarantine them before introducing them to aquariums with existing Acropora

spp. The quarantine period should involve close observations preferably

with a magnifying lens to look specifically for this invertebrate

Management or Mitigation:

A treatment of red bug disease caused by T. acroporanus, first developed by Dorton (2010), is the use of Milbemycin oxime,

an active ingredient in heart worm medication for dogs called

“Interceptor” within the USA or in a product called ‘Milbemax’ in the UK

(where M. oxime is mixed with Praziquantal). This is an indiscriminate drug which kills all crustaceans as well as T. acroporanus,

so would not be a feasible treatment of wild diseases or aquaria with

mixed communities including crustaceans (crabs, lobsters, shrimp). An

attractive option to this treatment is the introduction of a biological

control, the dragonface pipefish, Corythoichthys haematopterus for example. These fish are known to anchor themselves to Acroporids and feed on crustaceans including T. acroporanus. It is also common that secondary infections often follow, initiating from the feeding scars caused by T. acroporanus, along with the scars left by nudibranchs, Drupella and/or other corallivorous snails.

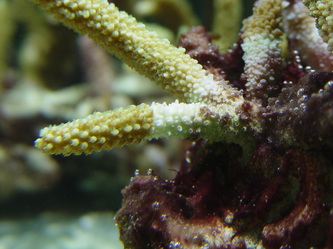

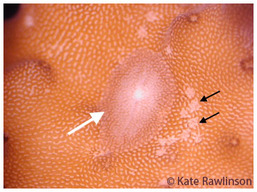

Acropora Eating Flatworms

Background:

Adult (white arrow) with feeding scars (black arrows)

The

Acropora-eating flatworm (AEF or AEFW) is a common predator of aquarium

Acropora species.They consume coral tissue and are extremely

well-camouflaged. On first glance, the only visible sign of their

presence is feeding scars, which expose the coral skeleton. Feeding

lesions may be misdiagnosed as other syndromes (potentially classed in

the WS group), and so the impact of this predator in the wild is not

fully appreciated.

Causes:

Although a problematic Acropora

predator in aquaria for over 10 years, very little was known about the

AEFW, it's biology or taxonomic affinity until last year when it was

named Amakusaplana acroporae (a polyclad worm belonging to the

phylum Platyhelminthes) and information on its life history was

described (Rawlinson et al. 2011). As this parasite is now widely

distributed in the marine aquarium industry it is easily transferred

between aquaria by the exchange of cultivated colonies. Great care

should be taken when receiving Acropora colonies from another collection to quarantine them before introducing them to aquaria with existing Acropora

spp. The quarantine period should involve close observations to look

specifically for this small flatworm (adult size: ~ 1cm), it's feeding

scars and egg batches which are laid on the bare coral skeleton.

Management or Mitigation:

Eggs batches on coral skeleton (photo by J. Weatherson)

For

the treatment of flatworm infections, including the AEFW, Salifert’s

Flatworm Exit, levamisole hydrochloride, freshwater dips (15 ppt for 3 m

max) and iodine-based dips like Lugols iodine, Fluke-Tabs (Aquarium

Products), and Trichlorfon (Dylox 80, Bayer A.G.) have all been reported

for treatment of infected corals (Carl 2008; Nosratpour 2008). However,

it is important to note that smaller polyp species such as the

Acroporids can rarely tolerate the use of freshwater dips and often

mortality occurs soon after treatment.

FlatwormStop is a new treatment from Zeovit which allows direct dosing of a full stocked reef aquariums. FlatwormStop is safe for all fish and invertebrates and it works to eradicate Acro Eating Flatworms by stimulating the immune response of Acropora corals.

Below is one Hobbyist Procedure for eradication of these pests.

1. Remove all Acropora corals from rocks including encrusted ones and scrape off encrusted left over coral parts on the rocks. Inspect each coral with a flashlight for 2 minutes outside of tank and water (a bit of air drying allows eggs to be easier to identify) and scrape any off eggs. Might be beneficial to cut the base off certain heavily infested corals and through out a others which have to many eggs.

2. Dip in diluted Revive solution (according to instructions) for 8-10 minutes for hardy Acroporas but 5 minutes for deep water Acroporas and other sensitive corals. Swirl corals initially in Revive solution then blast them with a turkey baster 5-10 times while dipping.

Be careful with deep water Acropora corals and others. Pearlberry, Ice Fire, and Hawkins Eechidna corals are especially sensitive as you can blast the skin off of them if you are too harsh.

3. Swirl and let sit in fresh saltwater after Revive dip for 10 minutes. Blast with turkey baster 3-4 times every few minutes. Return to tank but on sand bed.

4. Repeat weekly for 2 additional weeks.

5. Glue corals to small rock bases and reattach to live rock. Now check periodically for re infestation e.g. bitemarks and AEFW’s that may come off by blasting, etc. Use common sense.

6. Add a natural predator or two; e.g. Yellow Wrasse, scientific name Halichoeres chrysus, to form a biological AEFW control team with others such as the Six Line Wrasse. These guys like to eat a variety of small pests from corals.

FlatwormStop is a new treatment from Zeovit which allows direct dosing of a full stocked reef aquariums. FlatwormStop is safe for all fish and invertebrates and it works to eradicate Acro Eating Flatworms by stimulating the immune response of Acropora corals.

Below is one Hobbyist Procedure for eradication of these pests.

1. Remove all Acropora corals from rocks including encrusted ones and scrape off encrusted left over coral parts on the rocks. Inspect each coral with a flashlight for 2 minutes outside of tank and water (a bit of air drying allows eggs to be easier to identify) and scrape any off eggs. Might be beneficial to cut the base off certain heavily infested corals and through out a others which have to many eggs.

2. Dip in diluted Revive solution (according to instructions) for 8-10 minutes for hardy Acroporas but 5 minutes for deep water Acroporas and other sensitive corals. Swirl corals initially in Revive solution then blast them with a turkey baster 5-10 times while dipping.

Be careful with deep water Acropora corals and others. Pearlberry, Ice Fire, and Hawkins Eechidna corals are especially sensitive as you can blast the skin off of them if you are too harsh.

3. Swirl and let sit in fresh saltwater after Revive dip for 10 minutes. Blast with turkey baster 3-4 times every few minutes. Return to tank but on sand bed.

4. Repeat weekly for 2 additional weeks.

5. Glue corals to small rock bases and reattach to live rock. Now check periodically for re infestation e.g. bitemarks and AEFW’s that may come off by blasting, etc. Use common sense.

6. Add a natural predator or two; e.g. Yellow Wrasse, scientific name Halichoeres chrysus, to form a biological AEFW control team with others such as the Six Line Wrasse. These guys like to eat a variety of small pests from corals.

|

Photo of live Amakusaplana acroporae hatchling

Preventing Coral Diseases

Prevention

is mainly down to ensuring good water quality at all times, as well as

maintaining coral safety (from fish bites, falls and stings from other

corals) and clean corals (good water flow). Also ensuring standardised

temperatures and ultraviolet radiation. The need for good quarantine

procedures is important particularly if you donate or receive colonies

to or from other collections. It is important to have a good idea of the

potential pests and parasites to look out for but it is also necessary

to keep an open mind as there is always the chance of something

completely new appearing. If a novel parasite is suspected taking

pictures of it on the coral and of any damage it has done to the coral's

tissue is helpful. Preserving a sample of any suspected parasite in

ethanol can also help with identification but good notes about where and

when it was found, and on what species of coral is also important.

GREAT Preventative/precautionary measures

GREAT Preventative/precautionary measures

Freshwater Dip (for saltwater fish only)

The freshwater dip is probably the most common dip for saltwater species and will rid the fish’s body of many potential harmful parasites.

Parasites such as:

- Paravortex (the black spot disease a.k.a. black ick) which is caused by the turbellarian flatworm with a similar life cycle as “Ick”

- Cryptocaryon which is the marine equivalent to “ick” a.k.a. marine or saltwater “ick”

- Velvet or coral fish disease (similar life cycle as “Ick”) is difficult to diagnose due to a similar Ick-infested fish behavior, as well as the undetectable and highly infectious skin flukes (worms living on the fish).

Saltwater species have a constant exchange of fluids called osmosis, which in simple terms is when pure water dilutes the mineral and salt rich water in order to equalize. Freshwater will rupture the cells of the parasites instantly killing them in great numbers independently of the status of the reproductive cycle. (i.e. ick medications are only effective on the free-floating tomites).

The freshwater dip is very effective to rid the fish of parasites causing black ick, marine ick, velvet and flukes, but ineffective towards bacterial or fungal diseases.

The bath has to be prepared with pure water, preferably RO/DI, or as an alternative distilled water. The fish should be closely watched and the bath administered for 5-10 minutes.

Saltwater Dip (for freshwater fish only)

Fish stress is relieved and the organism can fight off diseases easier which aides in the recovery. The concentration should be 4 teaspoons per Gallon and the duration of the bath about 30 minutes. This bath will also stimulate the protective slime coat, which will further enhance the fish’s’ ability to cope with the disease.